The history of the World Cup is replete with tales of epic encounters. In 1950, Uruguay drove an ice-cold dagger into the footballing heart of Brazil when they lifted the trophy after beating the Seleção in the infamous Maracanazo. Twenty years later West Germany faced Italy in the 1970 semi-final as the two teams slugged it out like exhausted heavyweight boxers across a merciless 30 minutes of extra-time under the relentless Mexican sun. A dozen years later, the Azzurri featured in that epic contest against the Brazil of Socrates and Zico. In the same competition the gloriously artistic French team of Platini, Giresse, Tigana et al, were denied by the Teutonic efficiency of West Germany, aided by the scurrilously unpunished aggression of Toni Schumacher.

Also Read: Pints in Spain: When Leeds went toe to toe with the big guys of Europe

Few of those games can, however, match up to the star billing that lit up the game when the World Champions Uruguay who had declined to play in the World Cup in 1934 and 1938, and undefeated holders of the crown for some 24 years at the time, faced up to the 1952 Olympic Champions – a team on an unbeaten run of three-and-half years, almost 50 games and averaging four goals per game. It wasn’t Superman vs Batman, or the Avengers Infinity War, but it was getting there when, in the 1954 World Cup, Uruguay faced Hungary.

The early stages of the tournament had already indicated the sort of form that the Hungarians, so many people’s strong favourites to lift the trophy, were in. The previous year, they had visited Wembley and inflicted that humbling 3-6 defeat on the team that considered itself invulnerable to foreign opposition when playing at home. Then, in the final game before the tournament began, the Hungarians franked that form and underscored the new world order by thrashing England 7-1 in Budapest. It was the sort of form they carried into the tournament. In just two group games they amassed no less than 17 goals, defeating South Korea 9-0 and then West Germany 8-3, although the Germans would take revenge later.

Uruguay had suffered the relative humiliation of finishing in third place in the 1953 Copa America, when an unexpected defeat to Chile had cost them a place in the final. They still retained many of the players who had been successful in retaining their crown in Brazil four years earlier though, including forward Juan Alberto Schiaffino, soon to become subject of a world record transfer fee when moving from Peñarol to AC Milan following the tournament’s end, and their dominating centre half and captain, Obdulio Varela.

The World Cup offered Uruguay an opportunity to reassert their global supremacy. The South Americans had been a little recalcitrant in comparison to the goal glut of the Hungarians, amassing just the nine goals in their couple of group games. Scotland felt the sharp edge of the South Americans’ frustration, conceding seven times without reply after Czechoslovakia had restricted La Celeste to a mere two strikes.

In the quarter-finals, the Hungarians scored another four goals, conceding two in reply against Brazil in the infamous Battle of Bern, and the Uruguayans matched the Magical Magyars toll when facing England in their last eight tie, albeit in much less rancorous circumstances. It meant that when the two teams faced off with each of their pedigrees looking like a CV that any team would die for, Hungary had won their three games by scoring 21 goals, an average of seven per game, and conceded five, two of which had been late goals by the Germans when trailing 7-1 and 8-2. The World Cup holders had scored 13 times in their three games and conceded just two times.

In fairness though, this World Cup tournament was hardly a study in defensive expertise, with goals flowing. In the quarter-finals, Austria defeated Switzerland 7-5, after being three goals down, before losing to West Germany 6-1 in the semi-finals. By the time the two behemoths met in Lausanne’s Stade Olympique de la Pontaise, on 30 June, the 45,000 spectators were expecting to be royally entertained. They wouldn’t be disappointed.

Also Read: Josef Masopust: A golden career and 100 seconds of immortality

As well as a contrast between two teams, each with arguably logical claims to being the planet’s foremost footballing power, the game would also inevitably feature a clash of cultures as the South American pattern of play rubbed up against the dynamic Hungarian system. At the time, with intercontinental travel still a major problem, there was precious little interaction between teams from the different continents and World Cups were serially won by teams from the host hemisphere. Brazil’s victory in Sweden at the 1958 tournament was the only time this trend was bucked, arguably until Brazil’s 2002 victory in Japan. There was, therefore, still a measure of mystery when teams clashed in this manner.

The Hungarian pattern, playing with what has latterly been termed as a ‘False Nine’ usually in the guise of the astute Nándor Hidegkuti, predating any kind of assumed tactical genius of Guardiola’s Barcelona around fifty years later, was a key innovation. The ploy created space in the midfield and fluid attacking options. Although the tactic invariably provoked problems for opponents – not least England whose defence had been torn asunder by the rampant Hungarians – the Uruguayans had the players with flexibility to counter the move. Varela would be absent through injury, and replaced by Néstor Carballo who, similar to his captain would not feel out of place advancing to close down a deep-lying opponent.

Hungary were also denied the services of their captain, with Ferenc Puskás also on the injured list. His absence, however, did allow coach Gusztáv Sebes to bring in Péter Palotás, who had played in the Hidegkuti role. As the two dropped deeper, space was opened in the middle for the likes of Zoltán Czibor to exploit, with the Uruguayan centre half drawn out of position. It would lead to the opening goal of the game, as the rain poured down, slicking up the playing surface.

In their previous three games, Hungary had been quick out of the blocks to try and establish a domination of the game and an early lead. Against South Korea, Puskás had scored after a dozen minutes; consequential games would make that strike appear tardy. Against West Germany Sándor Kocsis had netted the first of his four goals of the game with just three minutes on the clock. The early strike rate was then maintained against Brazil as Hidegkuti gave the cherry-shirted Europeans the lead after four minutes. It was a ploy that Sebes insisted on against Uruguay as well.

In the Uruguayan goal, Roque Máspoli, was in for a busy first dozen minutes or so. First Palotás tested the vastly experienced Peñarol goalkeeper drawing a sharp save from the 36- year-old, and then Jozsef Bozsik, standing in as skipper for the absent Puskás, and somewhat controversially allowed to play in this game despite being dismissed in the battle against Brazil, fired narrowly wide. The nearest to an early goal came from Hidegkuti. Shooting from a tight angle, his effort scraped past the post with Máspoli beaten and Czibor in presumptuously celebratory mode, before reality and anguish subdued his ardour.

Also Read: Arthur Friedenreich: The Pelé before Pelé who became Brazil’s first superstar

When the twelfth minute arrived without a breakthrough for the Europeans, Uruguayan coach Juan Lopez may well have been relieved as his side eased their way into the game, but a goal was imminent. The deep-lying Hidegkuti had found his usual parcel of space in midfield and picked out Kocsis with a neat lofted pass. Spotting the penetrating run of Czibor, the Honvéd forward who would later escape the invasion of his country by the Soviet Union to achieve legendary status in Barcelona, nodded the ball into the Uruguay penalty area for his team-mate to run onto. With his marker befuddled by the move, Czibor collected and shot from around 12 yards. His effort was scuffed, however, and surely should have been saved, but somehow Máspoli contrived to allow the ball to bobble past his outstretched hand and into the net. The Hungarians were ahead.

Perhaps, sated by the strike or lulled into a false sense of security by the memory of how so many of their opponents had folded after falling behind to an early goal, and undoubtedly to Sebes’s great chagrin, the Hungarians seemed to ease off from their busy start and Uruguay found a way back into the game. In contrast to the Hungarians fluid play, the South Americans sought to open up their opponents’ back line with astute passes and runs into space. Now with more possession than in the opening period, Uruguayans compelled the defensive pairing of Mihály Lantos and Gyula Lóránt to demonstrate their calm assurance, although they were often compelled to merely hack clear under pressure, and goalkeeper Gyula Grosics was frequently required to advance from his line to follow suit when passes evaded the duo. Probably the best chance to equalise fell to Schiaffino when he managed to go around Grosics in the area, but then failed to get off an effective shot.

After the ebullient opening from Hungary, the game was now fairly even as Uruguay pressed to level. The Hungarians lacked little in comparison though and their intricate play opened up chances as well. A goal for either side would be crucial in the way the fortunes of the game swayed back and forth. It nearly came when a cross from the left found Kocsis unmarked around ten yards from goal. His header was powerful but poorly directed towards the centre of the goal, and Máspoli leapt to divert it over the bar with his left hand. There were no more goals before the break and both teams retired to their dressing rooms to take on board the words of wisdom from the respective coaches.

Uruguay began the second half, but if Lopez had emphasised the importance of not conceding early again, the advice was not heeded. Honvéd winger László Budai had been selected to play in place of the injured József Tóth, and during the first period, his pacey and tricky runs down the flank had been a thorn in the side of the Uruguayans, but inside 60 seconds of the restart, his play brought some tangible reward.

A cross to the far post found Hidegkuti hurling himself forwards to head powerfully past Máspoli and double the lead. Clearly shaken by the setback, Uruguay were like a dazed boxer on the ropes as Hungary pressed for another goal that would surely kill off the game. Shots rained in, but in contrast to his early error for the opening goal, Máspoli defied all of their efforts, and kept his team clinging on to a fingertip hold in the game. A penalty claim for a clumsy challenge on Hidegkuti looked to have merit, but Welsh referee Benjamin Griffiths was unconvinced.

Slowly clearing their heads, Uruguay demonstrated the resilience and refusal to bend the knee under the severest pressure that had seen them come back from a goal down in front of nearly 200,000 wildly partisan Brazilians in the Estádio do Maracanã four years earlier. Even without the driving force of their absent skipper and totemic leader, Varela, this was a team of character and no little ability. They were reigning champions of the world. With the elusive and slippery skills of Schiaffino becoming more of a factor as the game progressed and energy levels dropped, Uruguay showed they were anything but a beaten team. With 15 minutes remaining, a Javier Ambrois pass eventually found chink in the Hungarian back line and Juan Hohberg strode forward to coolly slot home and bring his team right back into the game. Although born in Córdoba, Argentina, Hohberg was a naturalised Uruguayan and as his shot rolled past Grosics’s left hand and into the net, the whole nation celebrated that fact.

Also Read: How Italy deployed the ‘Overload to Isolate’ tactic to overcome Netherlands

It was now game on, and for the remaining minutes, the Hungarian defence would be put under increasing amounts of pressure. Despite their flowing forward play, defence was often the disguised Achilles Heel of the Magyar team. Usually their forwards would score more than they conceded to minimise the effect of the less than perfect back line, but in Uruguay, they were playing against anything other than ‘usual’ opponents. Schiaffino was now in his pomp, prodding and probing for any other gap that could be exploited as the Hungarian defence battled to retain what had looked like a comfortable winning position.

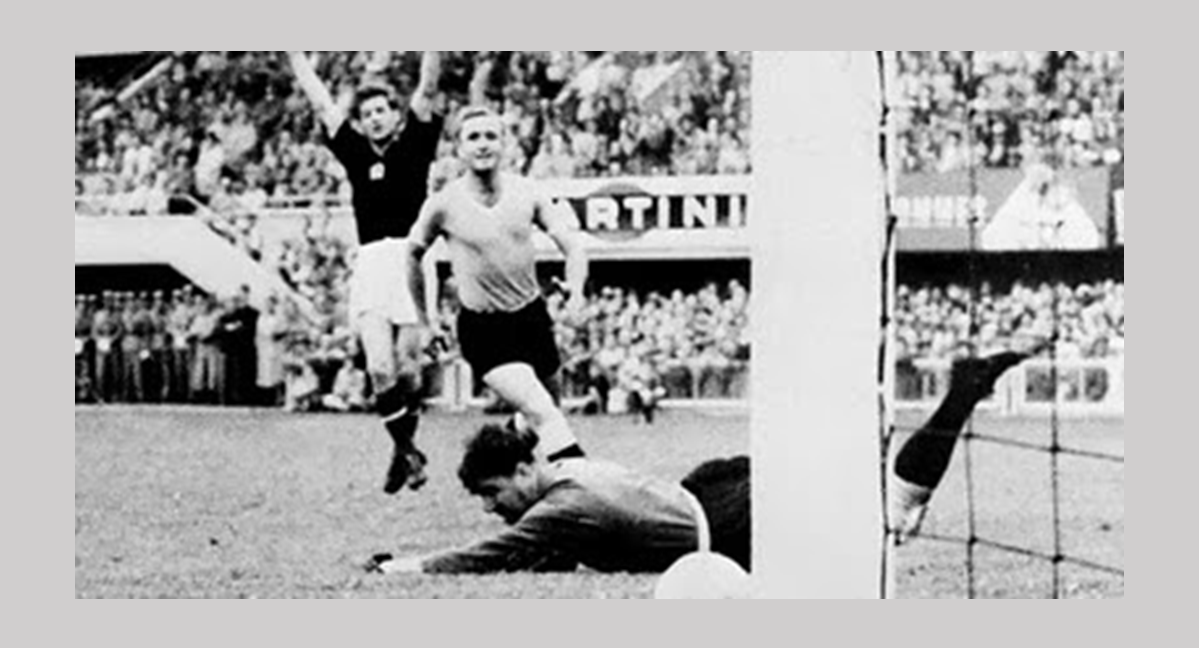

With just four minutes remaining, the dam finally broke as Hohberg again found space to break into the area and dribble around Grosics. Racing back to defend, however, both Lantos and Jenő Buzánszky took advantage of the delay caused by the goalkeeper’s challenge to drop back onto the line. Calmness personified, Hohberg merely paused before picking his spot high into the net beyond any despairing challenge. Hungarian head in hands. Uruguayan arms raised in both relief and celebration. It would surely be extra-time now with the South American wave of momentum poised to wash Hungarian dreams away.

With both teams comfortably winning their earlier games, albeit somewhat violently for the Europeans in their game against Brazil, neither team were used to being extended into an extra thirty minutes to decide a game. In such circumstances it is often resilience and resolve that decides the issue, rather than any particular outstanding piece of skill. With the reigning champions feeling that the game was there for the taking, they continued to press and Hohberg nearly completed a hat-trick when his shot deceived Grosics before striking the post. Even then, the goalkeeper was compelled to recover and throw himself forward to block a Schiaffino follow-up and divert the ball for a corner with his feet.

Hungary were forced to replicate the application that Uruguay had shown when two goals down and the game seemingly slipping away from them. There’s a time for effervescent forward play, and there’s a time to lock down and reassess. For the remainder of the first period of extra-time, Hungary opted for the latter. The decision would serve them well.

Four minutes into the second period, another cross from Budai found its target. In the second half of regulation time, Kocsis had headed straight above Máspoli requiring only a leaping save from the goalkeeper. This time, after out jumping Jose Santamaría, Kocsis guided his header well clear of Máspoli’s attentions and Hungary were back in front. Suddenly, it looked like the holders were the team in trouble again, and five minutes later, this time latching onto a cross from skipper Bozsik, it was another Kocsis header that decided the game.

Also Read: Book Review: The Games People Play

At the final whistle, the crowd rose to acclaim two magnificent teams, each who had seemed to have won and then lost the game as the momentum shifted between them with hypnotic regularity. Not only was it a battle between two legendary teams, but it had also been a magnificent contest.

Strange as it may seem, however, the game also marked a turning point for both teams. Uruguay’s unbeaten World Cup record had gone and the team would never be the dominant force that it had been since winning the Olympic title back in the 1920s and capturing the first World Cup, before repeating the feat in 1950. For Hungary, despite going 2-0 up early in the final against West Germany, they would eventually capitulate losing 3-2. Before losing that final, they had gone 31 games without defeat. After it, they played another 19 without losing, winning 16 and drawing three. They would have been strong contenders for the World cup in Sweden in 1958, but their team was torn apart and scattered to different parts of Europe when the Soviet Union’s tanks rolled into Budapest. They would never be the force they had once been.