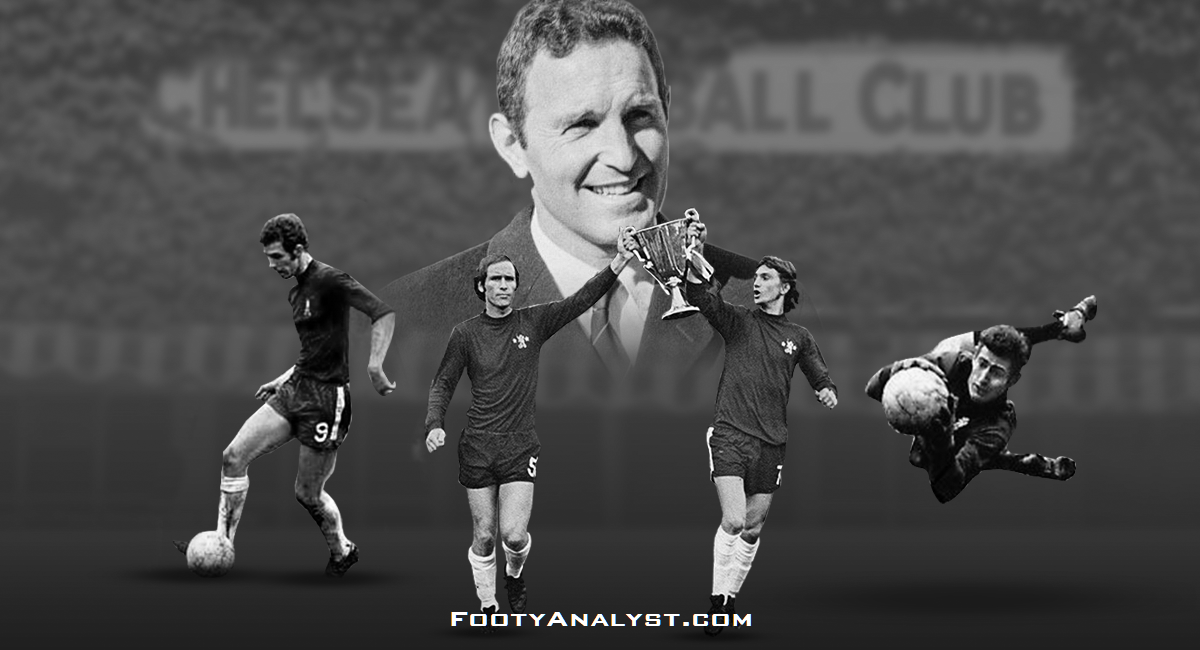

After winning the FA Cup in 1970, defeating Leeds United in a couple of brutal battles first at Wembley, and then in the replay at Old Trafford, Chelsea entered the European Cup Winners’ Cup. Under the guidance of their young and upwardly mobile coach Dave Sexton, the club were keen to prove their credentials of being more than a showy collection of flashy players more at home in Carnaby Street than on a football pitch. With the FA Cup victory suggesting the club were on an upward trajectory, European football was the ideal place to stake their claim. It was their first venture into European competition. It shouldn’t have been, but it was.

Having won the First Division title for the first time in their history in 1954-55, the West London club were invited to compete in the initial European Cup competition. A truculent Football Association, however, mindful of those pesky foreigners impinging on their jealousy guarded and outdated authority within the game, advised the club to demur, and Chelsea obediently followed the prescribed line. It was an error of epic dimensions, and the club would have to wait another 15 years before they could venture across the channel and become part of the continental scene. If an opportunity was missed in 1955-56, the chance offered in 1970-71 would be seized with both hands.

Also Read: Clive Thomas and “the most controversial decision that any referee has ever made”

The Cup Winners’ Cup was often looked down upon as the weakest of the European trophies on offer. Certainly, at this time, the European Cup, still very much the exclusive preserve of national champions, was the blue riband event, and the UEFA Cup, which also required league qualification wouldn’t get under way until the following season. This meant though that for any club missing out on the premier event, the Cup Winners’ Cup was the only other pathway to European competition. Certainly, in succeeding years, the quality of the clubs involved would be diminished somewhat by the advent of the UEFA Cup, but in 1971, it was a bumper crop of some of the continent’s most celebrated clubs.

Although at the time shed of the ‘Magical Magyars’ of the fifties, a mere pale shadow of the team that would surely have captured the European Cup save for the invasion of Hungary by the Soviet Union in 1953 that dispersed their players around western Europe, the name of Honvéd conjured up sufficient promise of technical wizardry. PSV Eindhoven, CSKA Sofia and Steaua Bucureşti were also involved, as were Bologna, Portuguese giants Benfica and the aristocrats of Spanish football, Real Madrid. Manchester City joined Chelsea as England’s representatives following their victory in the competition in the previous year, stamping their credentials with a League Cup Final victory over West Bromwich Albion.

Chelsea’s European Odyssey began in Greece on 16 September 1970. Ironically, it would reach its climax in the same country eight months later, and both games would initially end in a 1-1 draw, before being decided in favour of the Blues later. An Ian Hutchinson goal earned Chelsea a creditable if unspectacular draw when they opened their campaign in front of a reported 50,000 crowd on the Aegean coast against Aris Thessaloniki. Back in London, things were put to bed with a certain assurance. A comfortable 5-1 win with a rare strike from defender Marvin Hinton, and braces from both John Hollins and Hutchinson eased Chelsea through to the next phase.

In Round Two, Chelsea were pitted against the Bulgaria’s CSKA who had demolished the Finns of FC Haka 11-1 on aggregate in the opening round. Facing another long away trip for the first leg, this time they went one better than the draw in Greece. Tommy Baldwin wearing the absent Hutchinson’s number ten shirt sliding home the winner from a right wing cross just ahead of the break. Hutchinson would return for the home leg, but it was David Webb, reprising his goal scoring feat of the FA Cup Final Replay, who scored the goal to lock out the tie. Again, the goal came just before half time.

Also Read: The unexpected joys and controversy of Newcastle United and the 1969 Fairs Cup

Round Two of the competition also saw other fancied clubs pointed towards the exit door along with the Bulgarians. Honvéd were beaten home and away by Manchester City. Steaua Bucureşti lost heavily to PSV Eindhoven, conceding seven goals across both legs without reply, and Benfica tumbled out after a penalty shootout against the East German side, Vorwärts Berlin.

The Quarter-Finals therefore looked an easier path, but there were still decent sides left in the final eight, including both Real Madrid, PSV and Manchester City. The luck of the draw however saw Chelsea avoid all of those potential complications, instead being paired with the Belgians of Club Brugge. If any Stamford Bridge fans thought this would be an easy stroll into the Semi-Finals, though, they would be brought up short.

There was a less than comforting feel to the team that Sexton sent out on 10 March 1971 in Brugge. The reassuring presence of Peter Bonetti was absent, replaced by John Phillips, and John Boyle was deployed in a defensive role. Up front both Peter Osgood and Ian Hutchinson were out and replaced by Tommy Baldwin and Derek Smethurst. The compact, but packed De Klokke was feverish, and much of the passion spilt onto the park as the Belgians’ physical approach threatened to knock the Blues off their stride and potentially out of the competition.

The home team’s star man was the Dutch striker Rob Rensenbrink, and he was a constant threat to the Blues’ defence. As it turned out, the margin of defeat could have been much worse, but a 2-0 defeat confirmed Chelsea fans’ worries and a big improvement in both performance and score line was required to turn things around at Stamford Bridge, two weeks later.

Back at the Bridge, Phillips was still Chelsea’s last line of defence, but in front of him, the back four looked much more solid, with Ron Harris returning to displace Boyle. Osgood was back to lead the line, with Baldwin still in for Hutchinson. Sexton also appeared to have modified his tactical approach following the first leg, pushing his players into a more direct style to pressurise the Belgian club’s back line and keep a high tempo to the game. Peter Houseman cut the arrears, but inside the last ten minutes, Chelsea were still heading for the exit door, trailing 2-1 on aggregate. With just eight minutes remaining though, Osgood notched the equaliser, forcing extra-time.

Although Brugge had carried a threat throughout the ninety minutes, they appeared a spent force in the extra-time period – perhaps Sexton’s tactics had emptied their fuel tanks. Baldwin hit the bar, then the elegant Alan Hudson cleverly set Osgood up for the lead goal before Baldwin netted to close things out. It had been the first, and would be the only, time Chelsea had been asked to battle back from being behind in the tournament, and they had demonstrated the sort of resilience every team entering a Semi-Final needs.

Also Read: Ray Clemence: The White Hart Lane Years

Those qualities would be required in abundance when the last four pairings pitted Chelsea against Manchester City. For the only time in the tournament, Chelsea would play the home leg first and with the added pressure of it being a ‘domestic’ battle, a victory was even more important. A Derek Smethurst goal early in the second half was a slender advantage, but at least it was a lead to take to Maine Road, and a goalkeeping fumble by City stopper Ron Healy dropping a seemingly harmless free-kick from Keith Weller into his own net when unchallenged, gave the home team too high a mountain to climb. In their first European adventure, Chelsea had reached the final of the Cup Winners’ Cup.

Whilst Chelsea had been dealing with domestic matters, in the other Semi-Final, Real Madrid had turned out the lights of PSV Eindhoven. A professional goalless draw in Holland, and then a 2-1 win at the Bernabéu when Pirri scored with just eight minutes remaining to put the Spaniards ahead on aggregate was sufficient for Los Blancos to progress. The goal wiped out the away goals advantage given to the Dutch when Wim van den Dungen’s strike equalised the opening Madrid goal by local boy Ignacio Zoco.

It meant that Chelsea, European novices, would face the club with the continent’s most successful record. The Stamford Bridge club would be hunting their first triumph, Madrid were chasing their seventh. The clubs would meet at the Karaiskakis Stadium, Piraeus on 19 May 1971 to decide who would lift the Cup Winners’ Cup. That outcome wouldn’t be decided until two days later though.

For those who look for omens in such things, the nineteenth day of May has special significance for Chelsea. Written in number form it becomes 19/05, and the club was founded in 1905. No one knew it back in 1971 of course, but 41 years later on that same date, Chelsea would win the Champions League.

Real Madrid were the unrivalled aristocrats of European football and their manager Miguel Muñoz was very much a key element in their success story. As a player, he won three successive European Cups with Los Blancos, and then followed up by managing the clubs to two triumphs in the same competition, as well as countless domestic trophies both with his boots on and whilst sitting in the dugout. His team though, albeit scattered with legendary names, was aging. Francisco Gento, for example, was a veteran of the six European Cup triumphs who had played alongside Muñoz in their early years of domination. He was now 37 years old, and the end of this season would see him hang up his boots. A young, vibrant Chelsea team, under the innovative coaching of Sexton fancied their chances of taking the trophy back to West London, although most of the pundits favoured a Madrid victory.

Chelsea fans were delighted to have Peter Bonetti available for the final, and with a back four of John Boyle, John Dempsey, Dave Webb and skipper Ron Harris, there was a solid look to the back line. Although having Eddie McCreadie available to play as left back and Harris switched to the right may have been even more reassuring. In midfield, the solid John Hollins was in place to guard in front of the back four with Keith Weller, Alan Hudson, Peter Houseman and the dancing feet of Charlie Cooke primed to create for Peter Osgood. Sexton was looking to ensure his midfield wasn’t over-run and having Osgood as the lone striker in the truest sense of the word, was a price he was willing to play. If he was looking for a goal from Osgood, and then to see the game out with a clean sheet, the game came so close to playing out precisely that way.

Also Read: The ill-fitting shoe: Dennis Bergkamp at Inter

Early on Chelsea pressed and although Real Madrid contained the initial thrusts, the London club looked the more likely to score, with the Spanish threat largely confined to counter-attacks. For all their enthusiastic play though, Chelsea couldn’t find a way through the Spanish defence and the half-time break came and went with the scores still level. Ten minutes later though, that would change.

A succession of balls into the Madrid box had led Osgood to challenge the Madrid defenders causing problems, but without the ball breaking to Chelsea’s advantage. In the 56th minute their luck changed. Another ball into the box pinballed against a couple of defenders before falling neatly to Osgood. The centre-forward pivoted and drove the ball firmly past Jose Luis Borja and inside the post to give the London club the lead, doing a forward roll in celebration before being mobbed by ecstatic team-mates. Just more than 30 minutes remained for Real Madrid to rescue the game. It was barely enough.

Inevitably, as time ebbed away, Chelsea sunk further and further back, intent on protecting their led. Osgood became largely a peripheral figure, at least as a striker, with much of the play concentrated in the half Chelsea defended. The Spanish team were still an outstanding unit and pushed into a need to score, they responded with enterprise and skill. White shirts suddenly become like magnets attracting the ball as they pushed and probed to create openings, but Sexton’s men repelled each thrust with determined vigour. Just when it seemed that the Blues would hold out though, in the final minute, a scramble in the goalmouth, and an unfortunate error by Dempsey, saw Ignacio Zoco bundle the ball over the line.

It was heartbreak time for Chelsea. They had come so close to securing the trophy in their first trip into European competition, and now their lead had vanished. Inevitably, heads dropped and the dynamism of their early enterprise couldn’t be rediscovered in the extra 30 minutes now in play. The Spaniards were now in the ascendency and looked by far the more likely to score again. They also struggled to create another opening though, perhaps spent by their pursuit of the equaliser. Time drifted away and the game ended level. Penalty shoot-outs to decide finals were a thing for the future and so a replay was required.

Hasty arrangements swung into gear and the game was set for 48 hours later. Whilst fans from both clubs had swelled the attendance in the first game to some 45,000 – including more than 5,000 donned in Chelsea blue – inevitably large numbers couldn’t stay in Greece for the unscheduled replay. Although tales of determined Blues’ fans sleeping in the streets just to be around for the replay, later became the stuff of legend. For all that, when the teams returned to the Karaiskakis Stadium two days later, huge gaps in the stadium told their own story. There were less than 20,000 in the ground to see the fate of tournament settled.

John Hollins had been a major doubt for the first game, and tales in the newspapers ahead of the final revealed that, only following a robust fitness test, with manager Sexton dishing out some meaty challenges on his midfielder, was Hollins deemed fit to play. Another, game two days later, however was simply too much. Hollins missed the replay and Sexton shuffled his pack, with Hollins moving to a seat alongside Kenneth Wolstenholme in the commentary box.

Also Read: Chris Nicholl: Own goals, a great goal and the heavy price to pay

Tommy Baldwin came in to replace the missing midfielder. The move also offered support to Osgood up front. Baldwin was hardly regarded as a star in the Chelsea team, but the Gateshead born player was a redoubtable character, typical of the area of his birth. He wouldn’t let anyone down, and his record of 73 goals in 187 league games for the club illustrated his value as a goalscorer, and he had already made significant contributions in Chelsea’s pursuit of their first European trophy.

Muñoz also looked to freshen up his team. Argentinian midfielder Miguel Pérez was dropped from the starting eleven and replaced by wide man Manuel Bueno. Even with Pérez missing, however, there was still a non-Spaniard in the Los Blancos team, with Paraguayan Sebastián Fleitas drafted in to replace the veteran Gento, and attack down the flanks.

After seeing his initial plan foiled at the last, and pundits now even more convinced that Chelsea had missed their chance, with the final now there for Madrid’s taking, Sexton tweaked his tactics. The addition of Baldwin allowed a more progressive approach, and it would bring dividends for the men in blue. The Chelsea manager had tried to ensure his players were on the front foot to avoid the sort of traumatic last 30 minutes of the initial game and the period of extra-time, when Real Madrid had dominated the game. It seemed to work out.

With Osgood now having company up front, as Baldwin buzzed busily between an advanced midfield and supplementing the front man, Chelsea looked dangerous, When the first goal came though, just past the half-hour, it was from an unlikely source. Keith Weller played an arching clip towards goal from the right flank, that was helped over the bar by Borja.

Charlie Cook floated the corner in, and after an initial header towards goal was nodded clear, John Dempsey, up from his guardian position at the back to add some height and power to the attack, fired in a ferocious volley. It brought instant redemption for any perceived culpability in the Madrid equaliser two days earlier. Although the television initially suggested incorrectly that Dave Webb had scored, the Chelsea fans that had extended their stay in Greece hardly cared who had scored. Chelsea were ahead again and deservedly so. In the first game, the lead goal had invigorated the Spanish team. This time, however, Chelsea would double their advantage before Real Madrid had an opportunity to strike back.

Just six further minutes had passed when Baldwin gathered a pass from Harris. Driving forwards, he played the ball on to Osgood towards the edge of the penalty area, running forwards himself for a return, attracting defenders towards him. Utilising the brief moment of extra space, Osgood checked to the right and swept the ball into the far corner of the net. Chelsea were now two goals clear, and Real Madrid would have it all to do to pull the advantage back. In the commentary box, Wolstenholme turned to Hollins and asked, “So, John. Do you think that Chelsea can relax now?” Showing admirable restraint, the midfielder calmly replied, “I don’t think so.”

Also Read: Matthias Sindelar: The exquisite life and mysterious death of Austria’s ‘Papery Man’

Of course, Madrid pressed, but with the second goal to offer extra reassurance, Chelsea looked less nervous than when defending a single strike two days earlier. The experience may well have played into a growing confidence. Half-time came and went, and there was barely 15 minutes remaining when a fortunate ricochet saw Fleitas burst clear towards the Chelsea box. He drifted past a covering defender and fired home inside Bonetti’s near post. The goalkeeper could probably have done better, but that was a matter for debate, and Real Madrid had no time for such niceties. Surely, Chelsea couldn’t let a lead slip away again.

Sexton removed Osgood, adding the fresh legs of Derek Smethurst, but everyone knew that the denouement of the game would be decided in Chelsea’s defensive half of the field, regardless of what the South African forward could do. And that’s precisely what happened. Real Madrid huffed and puffed, but could not blow down the blue wall in front of Bonetti. Webb and Dempsey headed clear, whilst Harris and Boyle defended the flanks. The midfield scurried around to deny space and Real Madrid simply ran out of times, not to mention ideas. It was full-time and Chelsea had won the Cup Winners’ Cup with their first journey into European competition.

Skipper Ron Harris collected the trophy, and every one of the Blues’ fans who had stayed over, slept rough, risked jobs and the wrath of wives and girlfriends considered it all worthwhile. Following their FA Cup triumph of the previous season, Chelsea seemed set for a continuing upward swing in their fortunes. Such things seemed not to be part of the club’s DNA though, certainly not in those days, anyway. There would be relegations to endure and promotions to offer the promise of better things to come, before another major trophy was secured with the FA Cup victory over Middlesbrough in 1997. In the intervening period though, Chelsea fans had memories of that night in Greece, when the European debutants downed the continent’s most celebrated club to lift the European Cup Winners’ Cup.