The history of football in the latter years of the 1950s and the early ones of the following decade is dominated by Real Madrid in European club football and the Seleção Brasileira on the international stage. It propelled the names of players such as Alfredo Di Stéfano, Francisco Gento, Ferenc Puskás, Pelé and Garrincha into legendary status. Had things been slightly different, and but for a bad break or a kinder turn of fortune, some of those names may well have been supplanted by that of Robert Jonquet.

Also Read: When little guys dream big: How a small town club from Luxembourg went to the ball in Europe

The Frenchman was the captain of the Stade de Reims team, twice beaten by Real Madrid in the final of the European Cup, and also led the French team who were drawing 1-1 with Brazil in the semi-final of the 1958 World Cup after 35 minutes, before a clash with Vavá left him with a fractured fibula. With no substitutions allowed, after having a painkilling injection at half-time, he played out the rest of the game, posted out on the left flank as a hobbling passenger and France were beaten.

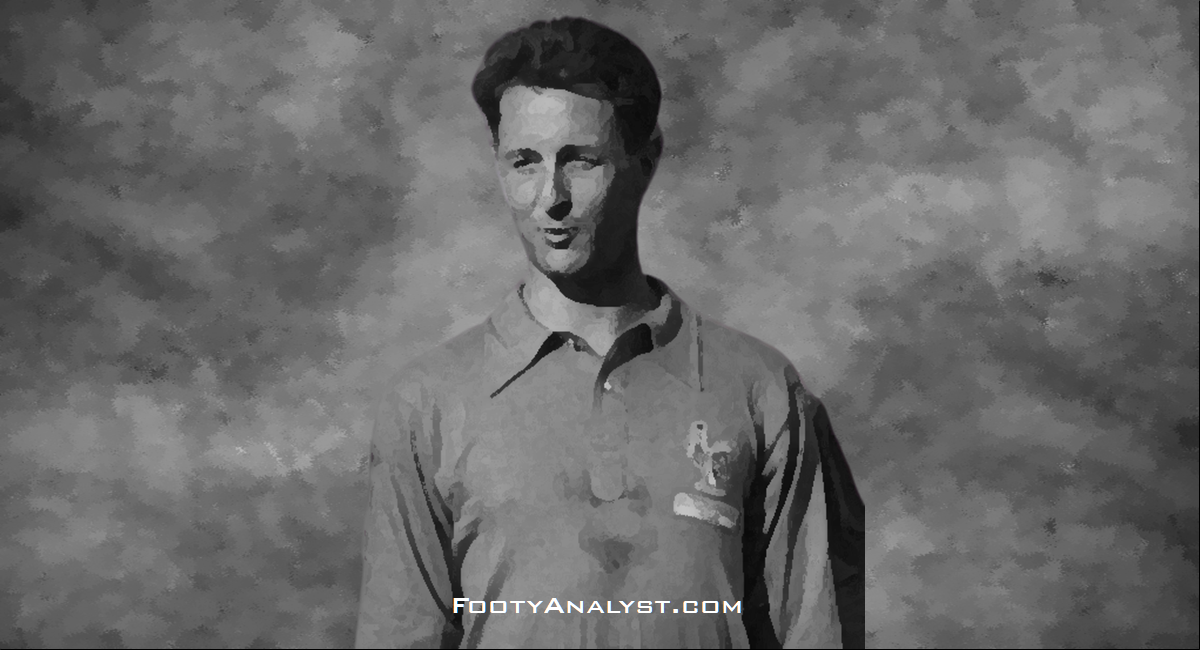

Despite coming within touching distance of fame and glory, however, there is far more to the career of a truly outstanding footballer. A revolutionary tactician, he would redefine the role of a centre-half in the football of his era. Standing a mere 5’ 10” tall, he made up for any lack of height with timing and anticipation, allowing him to intercept passes and intelligently bring the ball out of defence to set up attacks. It was the manifestation of an oft-espoused theory that despite being a defender, “Football is made to create, not to destroy.” In an era when defenders were there merely to defend, Jonquet was a man ahead of his time.

Robert Jonquet was born in Paris on 3 May, 1925. An enthusiastic and gifted sportsman from an early age, his natural speed made him an ideal athlete and, together with an interest in sailing, his sporting career could have taken many different courses. Football, however, was always his first love and he joined the local junior club Le Plessis-Robinson aged 12, where he would stay for four years before moving on to Châtenay-Malabry and then SS Voltaire-Paris.

In 1942, Jonquet’s father moved the family north-east, to the city of Reims, midway between the French capital and the Belgian border. A businessman of sorts, Jonquet Senior first opened a hairdressing salon, and then a café, as he sought to provide for his family in the troubled times of Nazi occupation and Vichy collaboration. Robert, however, wasn’t cut out for hairdressing and café work was never his cup of tea. Instead, he signed to play football for the city’s club, Stade de Reims.

It was the first step on an eighteen-year long journey that would see the club become one of European club football’s major powers, so nearly reaching its very summit, and the player who became its captain and inspirational leader, be acclaimed as one of the best players in Europe. The price paid for his signature was, reportedly, a new pair of football boots. It was a fee that Jonquet would not wantonly squander.

Midfielder Albert Batteux, six years the senior of Jonquet, was already an established member of the team when the 17-year-old arrived. In 1950, he would later become manager of the club ushering in an unheralded period of success for Stade de Reims, before also taking control of the French national team where, once again, Jonquet would flourish under his tutelage.

Also Read: CSKA Sofia: European football’s slayers of Champions

Released from six years of war and five of occupation, competitive football returned to France in 1945 and following an inevitable period of reintroduction, things were understandably slow to return to something bordering normality. By 1949, however, Stade de Reims and Robert Jonquet were moving forward, winning the French league title by a single point from Lille. They followed up that success the following season, winning the Coupe de France, defeating Racing Club de Paris 2-0 in the final at Le Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir, in Colombes. Les Rouges et Blancs were becoming a real force in post-war French football. The early success was merely the amuse-bouche though. After Batteux took over as manager later the same year, it would be time to prepare for the Hors d’Ouvre of domestic success and the Plat Principal of pursuing continental glory.

Jonquet was now not only a key member of the team, but also the trusted lieutenant of Batteux as the new manager built his side with Jonquet as the indispensable key element. The league title was secured in the 1952-53 season, as Reims finished four points clear of FC Sochaux-Montbéliard. The more striking statistic, however, was that the club’s defence. Marshalled and organised by Jonquet, it conceded a mere 36 goals in the 34-game programme. The 86 goals they scored in the same programme was also the best. It meant that Batteux’s team, now featuring not only Jonquet, but also the subtle talents of Raymond Kopa were not only worthy champions but also a growing force. It was both a remarkable record and something for Batteux to build on.

The Latin Cup had been inaugurated in 1949. It was widely considered as the successor to the pre-war Mitropa Cup, and forerunner of the European Cup. Featuring the league champions of France, Italy, Portugal and Spain, the hosts were rotated among the four countries involved as the competition ran until 1957, when the new European Cup competition rendered it largely redundant. Stade de Reims’ league title in 1949 was their invitation to take part in the tournament’s inaugural event to be held in Madrid. They would lose out in the semi-final to Barcelona, and then to a Torino team decimated by the Superga air disaster a month earlier, finishing in fourth place. It was Jonquet’s first taste of continental competition. Another league title for Les Rouge et Blancs in 1953 would give him another chance for European glory.

Travelling this time to Lisbon in June 1953, Reims were first matched with Spanish champions, Valencia, and defeated them 2-1 to gain a place in the final against AC Milan who had overcome hosts, Sporting Clube de Portugal. In a battle between red and white on one side, and red and black on the other, the French team came out comfortable 3-0 winners and took their first continental title, with Jonquet and his defence delivering another clean sheet. It whetted their appetite for more to come.

After finishing as league runners-up, losing out by a single point to Lille in 1953-54, they returned to the top of tree the following term winning the title by four points to Toulouse FC, with reigning champions Lille tumbling to sixteenth position. Another venture into the Latin Cup brought disappointment. The tournament was held at the Parc des Princes in Paris, but despite home advantage, and reaching the final, Reims lost out to Real Madrid. Over the coming few years, it would be a sadly repeated tale of disappointment against the Spanish club, both for Reims and Jonquet.

The European Cup took its bow the following term, with French magazine L’Equipe selecting the participants, not exclusively because they were champions of their various countries, but for being regarded as prestigious clubs and representative of their countries’ football. The first round was allotted rather than drawn, and with the final scheduled for the Parc de Princes, the fates seemed well set for Jonquet’s team. Success against the Danes of Aarhus, Vörös Lobogó of Hungary and Scotland’s Hibernian took them to the final, where they would meet Real Madrid again.

Ten minutes into the game and all seemed to be going well for Jonquet. Goals by Leblond and Templin had the French team in control and firmly on course to become the first club champions of Europe. Such exuberance was only permitted an ephemeral life. Four minutes after the second French goal, Di Stéfano put the result in doubt once more and, when Héctor Rial equalised on the half hour, all of the early dominance of Reims had been squandered, hopes and aspirations tempered. After the break though, Batteux’s team talk seemed to have injected new belief into his team and future French national manager Michel Hidalgo put them back in front just past the hour mark. Inside the last quarter, with the lead still intact, it was looking increasingly likely that Jonquet would be the first club captain to raise the new trophy but, as would be the case so many times in his career, at the crucial moment, fate turned its smile away from the Frenchman.

Also Read: Forgotten Franchises: Jack Gregory, Elton John and the story of LA Aztecs

On 67 minutes, Marquitos – grandfather of Chelsea and Spain international Marcos Alonso – found himself in an unfamiliar attacking position. As the ball came to him inside the area, he stumbled, bumbled and eventually forced the ball past René Jacquet, and into the net to equalise. Reports vary as to which part of his leg applied his final touch, some suggesting knee, shin and even thigh. The general consensus though was that it wasn’t his foot, and the final inadvertent contact was from a French defender. It’s a summary confirmed by video of the incident, as is the delighted surprise on the face of the inadvertent goal scorer.

It was the sort of conceded goal almost designed to convince Reims that it wasn’t their day. Sure enough, Rial scored again and the French challenge was over. The man who scored the winning goal would later reflect that, of the six European Cup finals he won with Los Blancos, this had been the hardest one they had ever played. Such comments are gracious of course, but would have been cold comfort to Jonquet and Les Rouges et Blancs. They had come so close, but not close enough. Fate would continue to deal such cards into Jonquet’s hands over the coming years.

Reims would have to go back to domestic football again in order to re-establish themselves. They did so when Jonquet lifted the Coupe de France for Les Rouges et Blancs in the 1957-58 season after beating Nîmes Olympique 3-1 in the final, and were also crowned champions of France once more, topping the table by a clear seven points from the same club they had overcome in the Coupe de France final. Success in the French Super Cup made it a domestic treble. Stade de Reims were ready to battle for glory against the continent’s top clubs once more.

By now, Kopa had moved to Madrid and was enjoying continued continental success with Los Blancos, and Reims were a different team from the loss in Paris in 1956. Jonquet was still the captain and leader at the back, but the front line was now led by the prolific Just Fontaine. The following season, they would again challenge for European Cup glory. Before that though, together with the other members of Les Bleus, Robert Jonquet would travel to Sweden for the 1958 World Cup with club manager Albert Batteux leading the squad. As well as captain Jonquet, and former ace Kopa, Stade de Reims were well represented in Sweden with six players making the journey to Scandinavia, including of course, Fontaine. It also included Jonquet’s former defensive partner at Reims, Roger Marche. He had moved to Racing Club de Paris in 1954, and missed the glory charge of Les Rouge et Blancs, but his understanding with Jonquet would prove invaluable to the French cause.

Jonquet had made his international debut back in 1948, and in 1952 following an epic display of defending in a game against England at Arsenal’s home ground, he was hailed by a newspaper as the ‘Hero of Highbury’. He would retain his position in the team right up to and including the opening game of the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland, where he captained the team that lost 1-0 to Yugoslavia, but then missed the 3-2 victory over Mexico. France had been eliminated at that first stage, but with another four years’ experience, and a side built around the success of Reims, the creative talents of Kopa and the goals of Fontaine, the portents for 1958 were much brighter.

Also Read: Giuliano Sarti – The ‘Ice Goalkeeper’

Ahead of that though, in 1955, alongside such luminaries of the European game as Austria’s Ernst Ocwirk, José Travassos from Portugal and Italian Lorenzo Buffon, Jonquet featured for a star-studded Rest of Europe select team against Great Britain in a match to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Norway Football Federation. It was another illustration that Robert Jonquet was now considered one of the best players in his position across the continent and, when the 1958 World Cup opened, expectations were high.

The French opened their account on 8 June with a group game against Paraguay. A comfortable 7-3 victory set them off and, with Fontaine securing a hat-trick, and Kopa providing chances for the forward line, aside from helping himself to a goal as well. It was a more than promising start. Throughout his career, Jonquet had worn the number five shirt for Reims, but with the squad numbering system, he was given the number ten shirt in Sweden. If the number was different, the role and performance differed very little.

Three days later, despite a further two strikes by Fontaine, France – sadly reprising their defeat from four years earlier – were beaten by Yugoslavia when Toza Veslinovic scored a late winner to hand Jonquet’s team a 3-2 defeat. It meant that they would now need to beat Scotland on 15 June to progress from the group stage. Goals by Kopa and, inevitably, Fontaine, had the French two clear, but a goal by Stuart Baird just ahead of the hour mark cut the deficit in half and put the game back into the balance. Jonquet and his defence held firm and kept the eager Scottish forwards at bay to see the game out. Thanks to their rout of the South Americans, France topped the group on goal difference from Yugoslavia, who had only managed draws against both the Scots and Paraguay.

Qualification took the French into a quarterfinal match against Northern Ireland in Norrköping. They would gallop through the game, winning 4-0 thanks to a brace from Fontaine, and one each from Stade de Reims teammate Roger Piantoni and Maryan Wisnieski of Lens. On the same day, in Gothenburg, Brazil edged past an unfortunate Wales team by a single goal thanks to a strike from an unheralded teenager by the name of Edson Arantes do Nascimento. Then the youngest player ever to feature, let alone score, in a World Cup Finals tournament he would, of course, later make his name in the final and become known to football fans around the globe as Pelé. France would play the youngster and his teammates in the semi-final on 24 June at the Råsunda Stadium, in the Solna district of Stockholm. France and their captain Roger Jonquet were one step from the World Cup Final.

Inside two minutes, disaster struck for Les Bleus. In typical fashion, Jonquet blunted a Brazilian attack with a perfectly timed sliding tackle. As the ball ran free, however, none of his teammates tracked the run of Vavá who was found free in the area with a perfect pass to fire past Claude Abbes. Lack of concentration by Jonquet’s teammates had cost them an early goal. Fortunately, they would soon be level. An acutely incisive pass by Kopa allowed Fontaine to skip around goalkeeper Gilmar, and bring the scores level. From that point the game was even and could have gone either way, with both sides having chances. Ten minutes before the half-time whistle though, the defining moment of the contest arrived.

An inadvertent collision between Vavá and the French skipper, saw the latter come off much the worse. The injury would later be diagnosed as a broken fibula and from that moment, the game was, to all intents and purposes, lost. Just three minutes later, the inevitability of that was illustrated when Didi restored the Brazilian lead. Half-time came and went, but there was little Batteux could do to change things. Heroically, but forlornly, Jonquet returned to the action placed out on the left flank, but it was, at best, now eleven players against ten plus a limping passenger, with a broken leg. The balance that had existed in the time between Fontaine’s equaliser and Jonquet’s injury was washed away.

Also Read: The Big Freeze of 1963: The last time when football was stopped for so long before COVID-19

Pelé added a further three goals, before Piantoni netted the least important of consolation goals inside the last ten minutes. From being on the cusp of a World Cup Final, Jonquet’s world had come crashing down around him and his teammates. The 5-2 result was as cruel and inappropriate a reflection of the difference between the two sides, as Jonquet’s injury had been to French aspirations. Les Bleus would not go as close to the biggest game in world football again until 1982. A few days later, they would defeat West Germany to secure third place, but Jonquet’s injury made him unavailable for the game. There would be one more major championship game for Jonquet in the blue shirt of France, albeit in a meaningless third place play-off, before international retirement. Ahead of that though, back in the red and white colours of Stade de Reims, there was the 1958-59 European Cup to contest.

Three years after its introduction, the competition had now gained much greater prestige, and few teams chose to ignore an invitation to compete – now rationed almost exclusively to national league champions. A comfortable 10-3 aggregate first round victory over Ards, with Fontaine netting no less than six goals, set Reims under way. It was followed by a 7-0 win across the two legs against HPS of Helsinki, with Jonquet returning two clean sheets to ease things along.

The last eight game was against Belgium’s Standard Liège and, despite losing the away leg 2-0, another clean sheet in the return, a goal from Piantoni and a brace from Fontaine saw Reims into the semi-finals. A similar pattern followed against Swiss champions Young Boys. A single goal defeat in Bern was turned around in the return with two goals from Piantoni and a third from Penverne. Another final against Real Madrid awaited, but this time, it was a disappointing performance as well as result. Fontaine had a rare ineffective game and, with their main goal threat misfiring, the French team became easy victims as Real Madrid added their third title in a row, winning 2-0.

Jonquet’s final international outing came, somewhat suitably in France at the 1960 European Championships. He had been absent for the semi-final game against Yugoslavia, when the French had conceded five times in a roller coaster of a game that they eventually lost 5-4. A play-off for third place followed at the Stade Vélodrome. Jonquet was restored to the team, but a 2-0 defeat to Czechoslovakia was a sad ending to an international career spanning a dozen years and 58 caps.

Also Read: When Johan Cruyff played in the 1974 WC with a two striped Adidas kit

The same year, also saw the end of the road for Jonquet at Stade de Reims. Now 35, with his best days clearly behind him, he moved to second tier Strasbourg, where he would later become manager for three seasons. In his first season with the club, he helped them to promotion in what was his final success as a player. He would return to Les Rouge et Blancs for a couple of tenures as manager without success, then on to brief spells at USM Romilly, RC Epernay and CO Châlons. He retired from the game as a coach in the 1980s, and returned to live in Reims. In February 2008, the club named a stand at the Stade Auguste-Delaune in honour of their former captain. In December of the same year, Robert Jonquet passed on.

It is perhaps both accurate and harsh that the potential status of greatness can turn on a few chance moments in a game of football. A fumbling equaliser in a European Cup Final; an unfortunate injury that costs your team a place in a World Cup Final. Had such events been different, the name of Robert Jonquet may have been as well known to football fans as other greats of the era. Such small difference can have huge consequences.