Considered by many pundits not only to be the best player in the world, Lionel Messi is also widely touted as the greatest of all time, but as success seems to follow success in an unending flow of glory and acclaim, it’s worth remembering that things weren’t always like that. In fact, as an 18 year old Messi entered the international playing arena for La Albiceleste on 17 August 2005, the game would be far from the triumph every young footballer dreamt of and prayed for, when pulling on the shirt of his country for the first time. In fact, it would be difficult to suggest how the fates could have conspired to be any more perverse.

Also Read: Johan Cruyff: The real founder of beautiful football (Part-1)

Well before that fatal August day, however, there was doubt that Messi would even play for Argentina at all, and if circumstances had been different, perhaps his mercurial talents would have been in Spanish Roja rather than Argentine Albiceleste. Although born in the Argentine city of Rosario, Messi had lived in Barcelona from the age of thirteen and the then Director of Football at the Camp Nou, Carles Rexach, had secured his services on that famous contract scrawled out on a paper napkin. It meant that Messi had eligibility to play for both Spain and his native Argentina, and Rexach was keen to promote his abilities to the Royal Spanish Football Federation in the hope that they would secure his affiliation.

Selection for Spain’s U17 squad was on the cards for a while. Rexach had used his influence to convince the selectors of the importance of locking down a talent he would later describe as “a player that was doing abnormal things from a young age.” An offer apparently followed to Messi and his representatives, but a proud son of South America, it was courteously declined. Like so many other aspiring footballers, as a child, Messi had dreamt of the day he would join the ranks of those honoured by the Argentine Football Association and called to the colours of his country. It was the sort of prayer offered up to the gods of football by so many aspiring footballers in Argentina, but so few of such entreaties are granted.

The AFA were quick to react and realised that they needed to do so with all due expediency. Had they hesitated, any second approach from the Spanish, in the absence of a move from Argentina, may well have received a more favourable response. To prevent any such occurrence, no matter how remote the possibility, the AFA organised two U20 Friendly games in June 2004, and used them to confirm Messi’s status as an Argentine international, locking out any further approaches from a covetous Spain. The games would be against Paraguay and Uruguay; the first being arranged a mere five days after Messi’s 17th birthday.

It was, therefore, less than a week after his birthday, when Lionel Messi confirmed to the footballing authorities something that had never been in any doubt in his own mind. He was an Argentine, and he would play football for Argentina. He debuted in the game against Paraguay, scoring once and creating two other goals in an 8-0 romp to celebrate his elevation to the Albiceleste. The performance was sufficient to convince the selectors to place him in the squad for the South American Youth Championship to be held the following February in Colombia.

If, however, there was now little doubt that he had the talent to play at the level, his physical attributes were less well honed. As well as his tender years, Messi had suffered with growth hormone deficiency and was therefore deemed to be lacking the strength and stamina that much of his older and more physically developed teammates had naturally acquired. It would be something to be addressed by a regime of training and other measures as time went on, but for that time, it meant a less than full contribution to the Argentine cause in the tournament. He would be named only as a substitute in six of the nine games Argentina contested in Colombia. After excelling in the game against Venezuela, however, he proved his worth in the most competitive of games when he scored the winning goal against Brazil that would guarantee Argentina a place in the World Youth Championship in the Netherlands a few months later.

When that tournament took place in June of 2005, Messi’s physical limitations had been largely addressed and a much more developed player was able to present himself for selection. Perhaps wary of the limitations experienced in South America though, and less than totally convinced of his improved physical condition, team manager Francisco Ferraro opted to omit Messi from the opening game against the USA. A 0-1 reverse, however, suggested that it was perhaps not the wisest of decisions. Consequently, for the remaining games of the group, against Egypt and then Germany, he was restored to the starting eleven, and the team delivered the required response with consecutive victories and outstanding performances from Messi at their heart.

Also Read: Marcelo Bielsa’s Argentina: Lost chances and broken hearts

With the group games successfully negotiated, Messi would increase his influence over the team, guiding them on to success. He would notch the important equaliser against Colombia then, much to the chagrin of his adopted homeland, score once and create a goal against Spain, before netting the opening strike against Brazil. It was now clear to all observers that Argentina had an outstanding talent, and the award of Golden Ball for the outstanding talent of the tournament was garnered ahead of the final against Nigeria. To confirm his importance, he would notch both goals in the final – each from the penalty spot – to secure a 2-1 victory and give Argentina their fifth championship. He would also finish as the tournament’s top scorer with six goals.

The player who had been considered too frail to complete a tournament, a few short months earlier, had now shown himself to be the outstanding talent in this age group despite the fact that, at on the cusp of his 18th birthday, he was still one of the youngest players there. A call up to the senior team was clearly on the cards, and it would not be long in coming.

If, however the experience in the Netherlands had been the very essence of answered prayers, the debut against Hungary in the Ferenc Puskás Stadium in Budapest would suggest the fates of football had decided to confirm the old Italian proverb quoted in Oscar Wilde’s 1893 book, ‘An Ideal Husband.’ Such being that, “Quando dio vuole castigarci, ci manda quello che desideriamo” (When the gods wish to punish us, they answer our prayers).” In the U20 World Championship, the success of Argentina and particularly of the young Messi fulfilled the prerequisite element of that equation. The accompanying punishment would follow in short order.

In Argentina, Messi’s selection to the full national squad had fuelled the already feverish speculation among fans that the heir to Maradona’s throne had been found. Many believed that he would start the game, and prove that the mantle of national footballing hero had now been passed on. Since the majority of the 27,000 fans in the stadium were Hungarian however, few of them would either have been aware of the expectation placed on the slight shoulders of the substitute wearing the number 18 shirt, or of the drama that would unfold when he entered the field of play.

Perhaps aware of the expectation heaped on the young Messi, manager José Pékerman had been a little circumspect and, with understandable caution, placed him on the bench. The clear intention being to invite him onto the pitch at a later stage in the game, rather than throwing him in from the start with a burdensome welter of expectation. Although both logical and laudable in concept, the plan would not produce the required result.

The second half of the game was heading towards its 20-minute mark when the call came for Messi to take the field. Argentina were leading 1-2 at the time, thanks to strikes by Maxi Rodriguez and Gabriel Heinze, with a reply from Sandor Torghelle falling between the two Argentine goals. Heinze’s strike had just restored the visitors’ lead when the call came from the bench, but the result would later pale into insignificance, as the most memorable event of the game would follow less than two minutes after Messi jogged onto the pitch to replace Lyon striker, Lisandro Lopez.

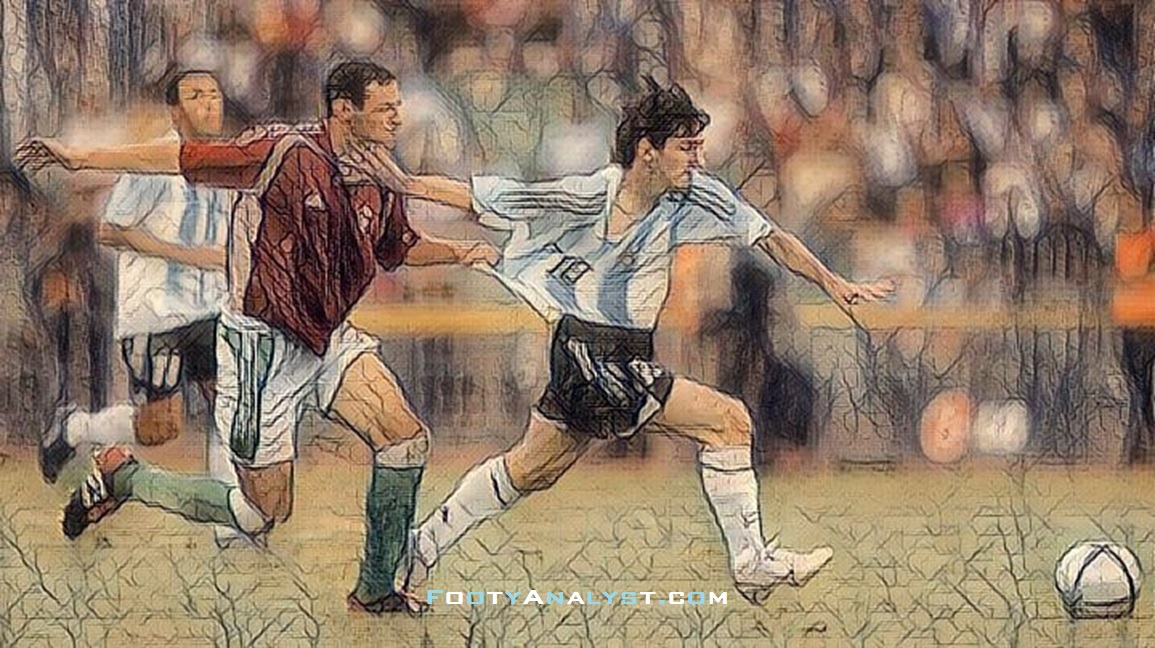

Eighteen minutes had elapsed of the second period, Messi was wearing an unfamiliar number 18 on his shirt, and he was eighteen years old. Such coincidences can often suggest a fortuitous outcome or, conversely, be the harbinger of dread fate. The latter would take hold in this instance. The first few seconds of his time on the pitch skipped by as Messi worked to get up to pace and become involved in the encounter. Then, a pass to him from Bernardi, halfway inside the Hungarian half, produced a neat turn to escape his marker, Vilmos Vanczák.

The Hungarian trailed after him, with an irritating hand tugging at the Argentine’s shirt as he headed goal wards. Trying to free himself, Messi flung back an arm, catching his assailant around the edge of his chin. The amount of force in the impact was perhaps up for negotiation, but as is the trend at such times, Vanczák fell to the floor holding his face in an area that seemed to be significantly different from the one struck by the Argentine arm. The referee whistled and Messi stopped clearly expecting a free-kick to be awarded to him for the blatant shirt-pulling offense, with the limit of any further action being a yellow card for the Hungarian’s misdemeanour. It was not the case.

Also Read: The ill-fitting shoe: Dennis Bergkamp at Inter

Quickly, a posse of Argentine players clamoured around the referee Markus Merk of Germany after the event. Did they fear that retribution from the Gods was forthcoming? Fevered arguments and remonstrations to the official suggest that they might have suspected things were not going in their favour. Vanczák eventually climbed to his feet to be shown a yellow card for the original offence, but the referee had not completed his disciplinary action. Walking around, trying to avoid the crowd of blue and white shirts forming a barrier, he eventually sought out the young Messi and, having decided that his swinging arm had been a deliberately violent act, brandished a red card. By trade, Merk was a dentist, and he had decided to extract Messi from this particular encounter.

Video of the incident shows Messi appearing genuinely surprised and then devastated at the decision, before turning and walking towards the touchline as his team-mates continued a fruitless and futile debate with the referee. Reaching the edge of the pitch, he was comforted by two Argentine officials as he walked down the tunnel and out of his international debut, some two minutes or so after entering it.

Reports suggest that he sat weeping in the dressing room for some time. His prayers had been answered in the Netherlands, his punishment had been delivered in Hungary. Messi would later lament that. “He came through me and had hold of me and I wanted to break free, but the referee interpreted it as though I had tried to shove him away.” Going on to explain that, “I went on with a lot of time left in the game, but then what happened, happened. It was not like I had dreamed it would be.”

Pékerman’s aide at the time, Hugo Tocalli, would later relate that although there were inevitably feelings of regret and disappointment, the player himself seemed calm. “It was all very simple, Leo was always very quiet, very reserved, did not express sadness, rather quiet and Jose gave him peace of mind at any time because he did not look nervous, he looked like he is now.” Tocalli would also recognise that support rather than sympathy was the balm required to soothe a troubled soul. “They are football things,” he reportedly told the teenager. “We are not going to change the opinion we have about you and you will be with us in the next game.” He was.

It was the sort of event that could blight any young player’s career, but fortunately, for Messi, there was a quick opportunity for redemption. On 3rd September, Argentina were scheduled to play a World Cup qualifier against Paraguay. It would have been easy and, to many, understandable, had Pékerman took the view that the red card followed an act of petulance by the player. Such things are always a matter of interpretation and perception of course. Had he done so, a period away from the squad to ‘cool his heels’ may well have been prescribed. The manager though had other ideas and selected Messi to play in what the player would label his ‘re-debut.’ The description displaying maturity beyond the player’s tender years, and a dedication to perform, that would be illustrated time and again throughout his future career.

Also Read: The Mozart of Barcelona: A farewell to Andres Iniesta

With the hiatus then behind him, Messi was selected to start the following qualifier against Peru and won a penalty which, when converted secured Argentine victory and propelled them on towards the World Cup Finals. After the game, doubtless with some measure of relief and a large dollop of satisfaction and anticipation, Pékerman would hail the youngster as a “jewel.” It may not have required the most astute of footballing brains to recognise the talented player Argentina had in their squad, but the wily manager did it anyway. The following year Lionel Messi would play in the World Cup Finals in Germany. The international stage that had seen but a fleeting glimpse of his talent on debut would now be treated to his presence on a regular basis.

Had the outcome in the Hungary game been some kind of celestial punishment for the earlier glory in the Netherlands? If so, it hardly put a stumble into the step of Messi’s ongoing career. A player seemingly granted God-given talent merely moved through such a dalliance with the fates, perhaps accepting the chastening experience as part of a required learning curve on the road to excellence. All football fans should surely give thanks for such resilience. Otherwise, the ebullient talent so often and widely celebrated may not have emerged, and football would have been a poorer place for its absence – regardless of any heavenly interference.